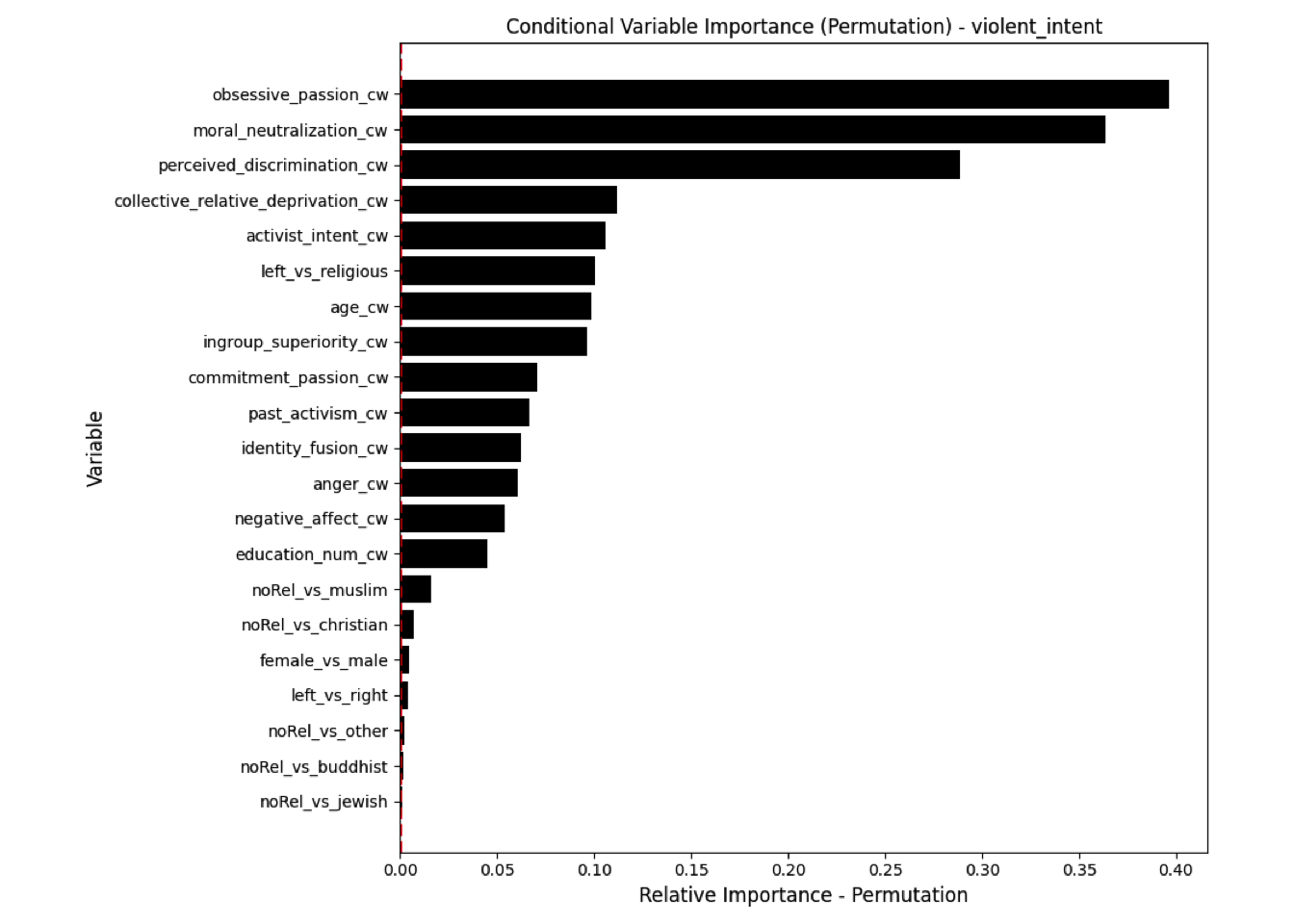

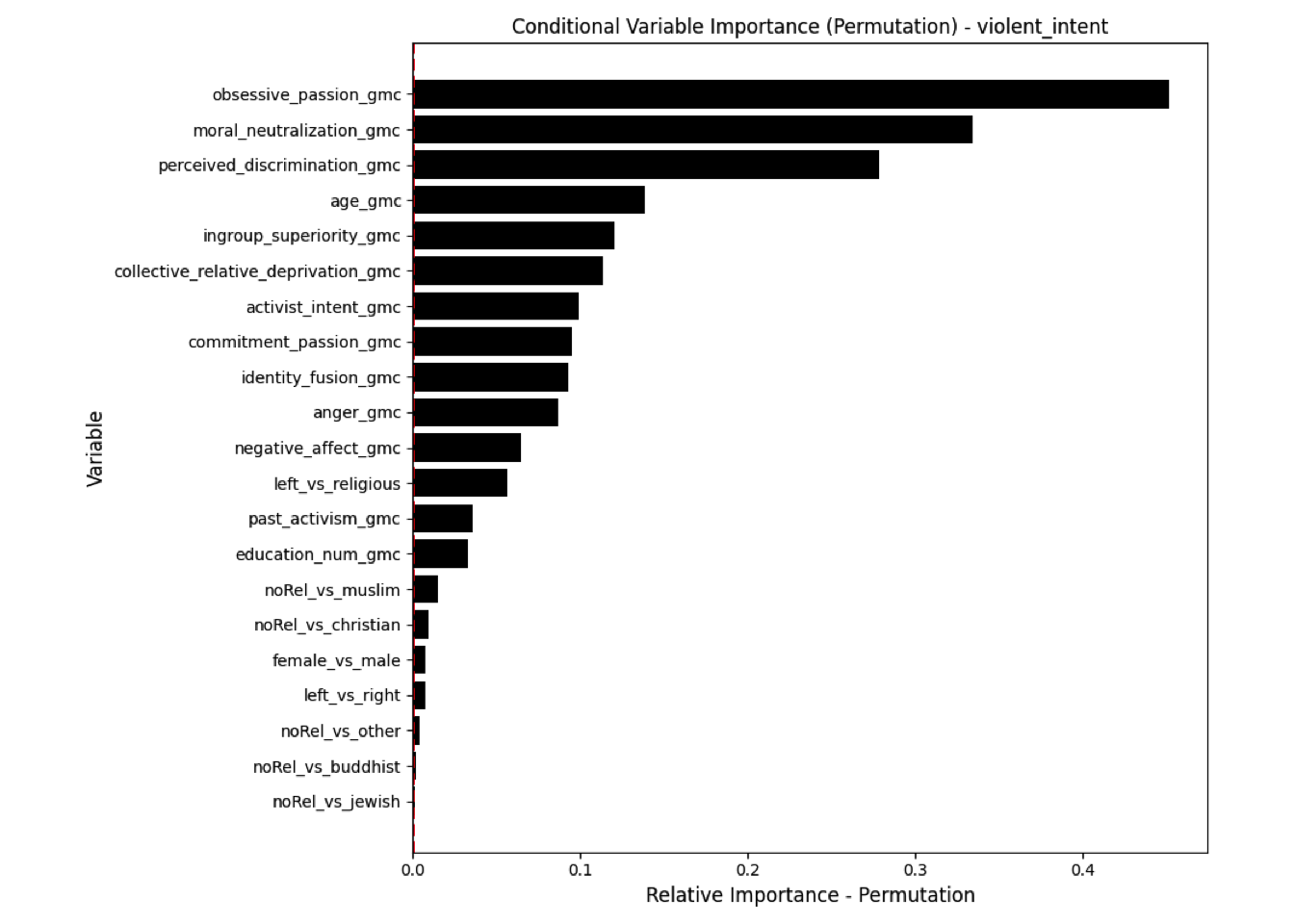

Conditional vs Unconditional Variable Importance

The following is copy-pasted from this wonderfull article. All credits go to the authors

: Debeer & Strobl, 2020.

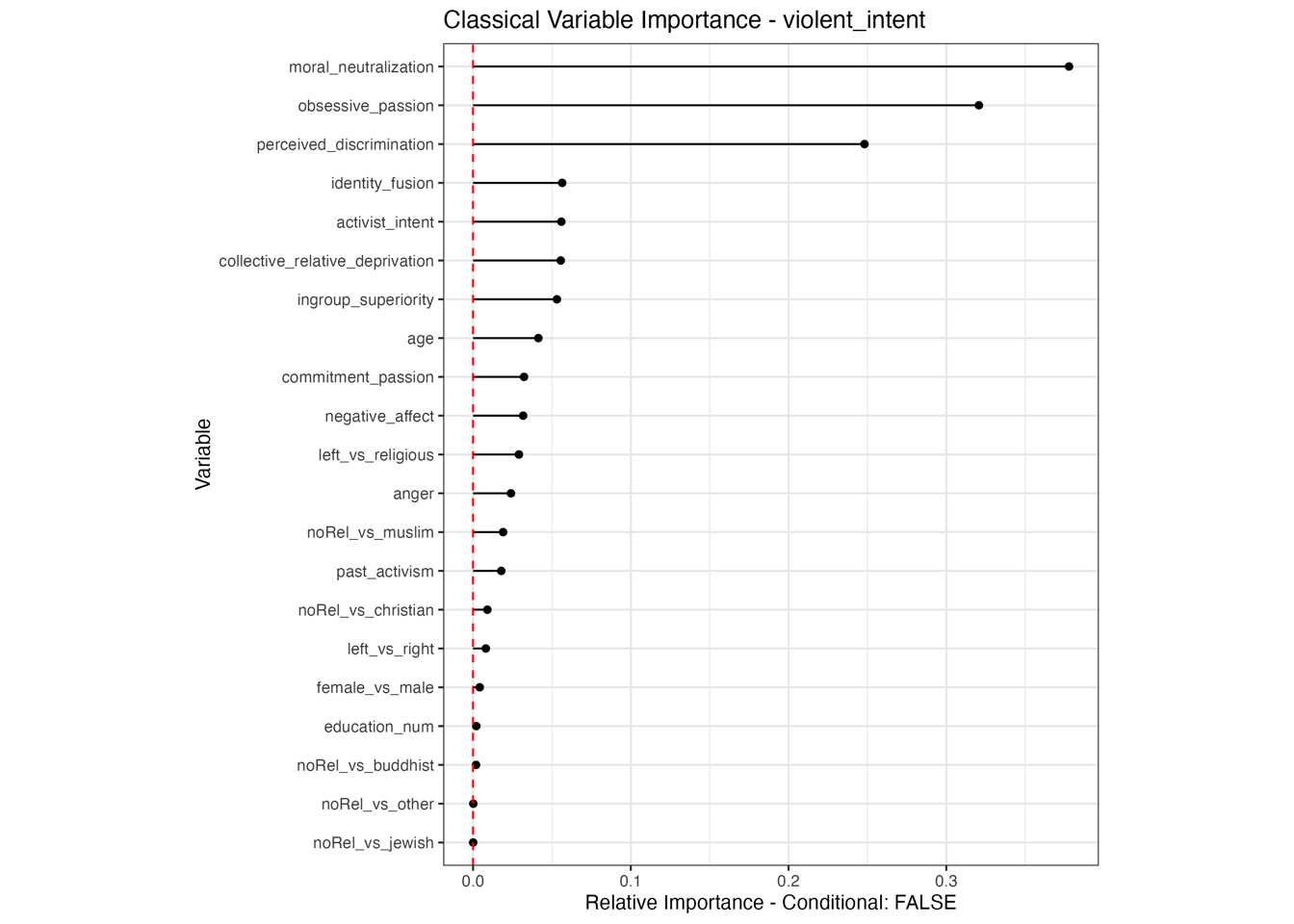

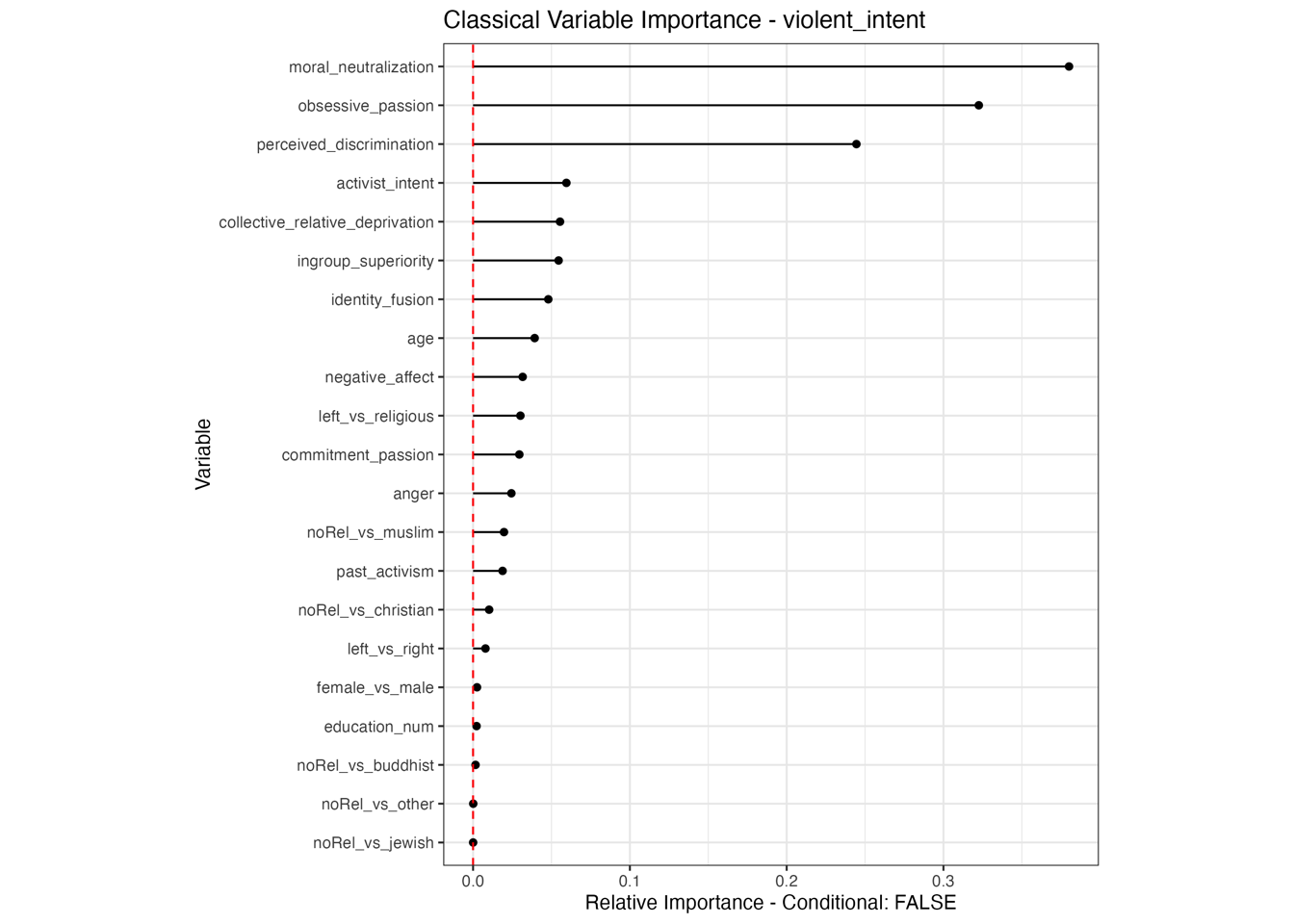

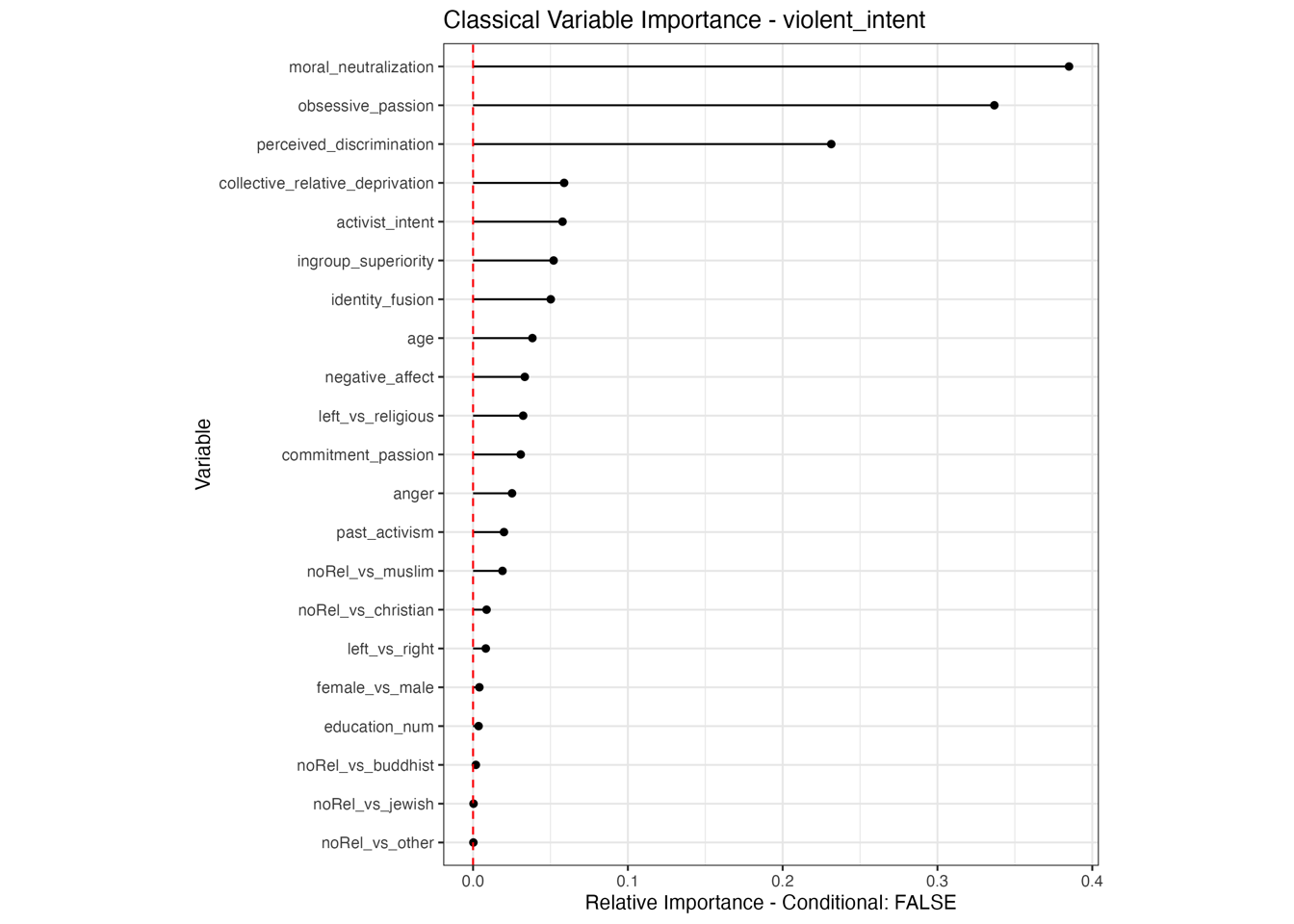

Because there is no consensus about what variable importance is or what it should be, it is impossible to identify the true or the ideal position for a variable importance measure on this dimension. Moreover, each researcher can subjectively decide which position on the dimension — and hence which proposed importance measure — best corresponds to his or her perspective on variable importance and to the current research question.

For a simplified example, consider the situation where a pharmaceutical company has developed two new screening instruments (Test A and Test B) for assessing the presence of an otherwise hard to detect disease. A study is set up, where the two screening instruments are used on the same persons. Due to time/money restrictions, only one screening instrument can be chosen for operational use. In this case, a more marginal perspective will be the preferred option to select either Test A or Test B. For instance, the test that has the strongest association with the presence of the disease (e.g., in the spirit of a zero-order correlation) can be chosen.

In contrast, let’s assume there already is an established screening instrument (Test X), and that the pharmaceutical company has developed two new screening instruments (Test A and Test B) of which only one can be used in combination with the established instrument Test X. In this case, a more partial perspective has our preference, as it assesses the existence and strength of a contribution of either Test A or Test B on top of the established Test X. For instance, the test that shows the highest partial contribution on top of the established Test X (e.g., in the spirit of a semi-partial correlation) can be chosen to use in combination with Test X.

For an alternative example, consider a screening study on genetic determinants of a disease. A variable importance measure in the spirit of the marginal perspective would give high importance values to all genes or single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are associated with the disease. Each of these genes or SNPs can be useful for predicting the outbreak of the disease in future patients. A variable importance measure in the spirit of the partial perspective, however, would give high importance values to the causal genes or SNPs but lower importance to genes or SNPs associated with the causal ones due to proximity. This differentiation can be useful to generate hypotheses on the biological genesis of the disease. Hence, the question whether the marginal or partial perspective is more appropriate depends on the research question.

Important for the application to random forests

The examples does not translate one to one, because random forests are not classical models but an ensemble technique. This being said, the basic logic of conditional versus unconditional still holds up.

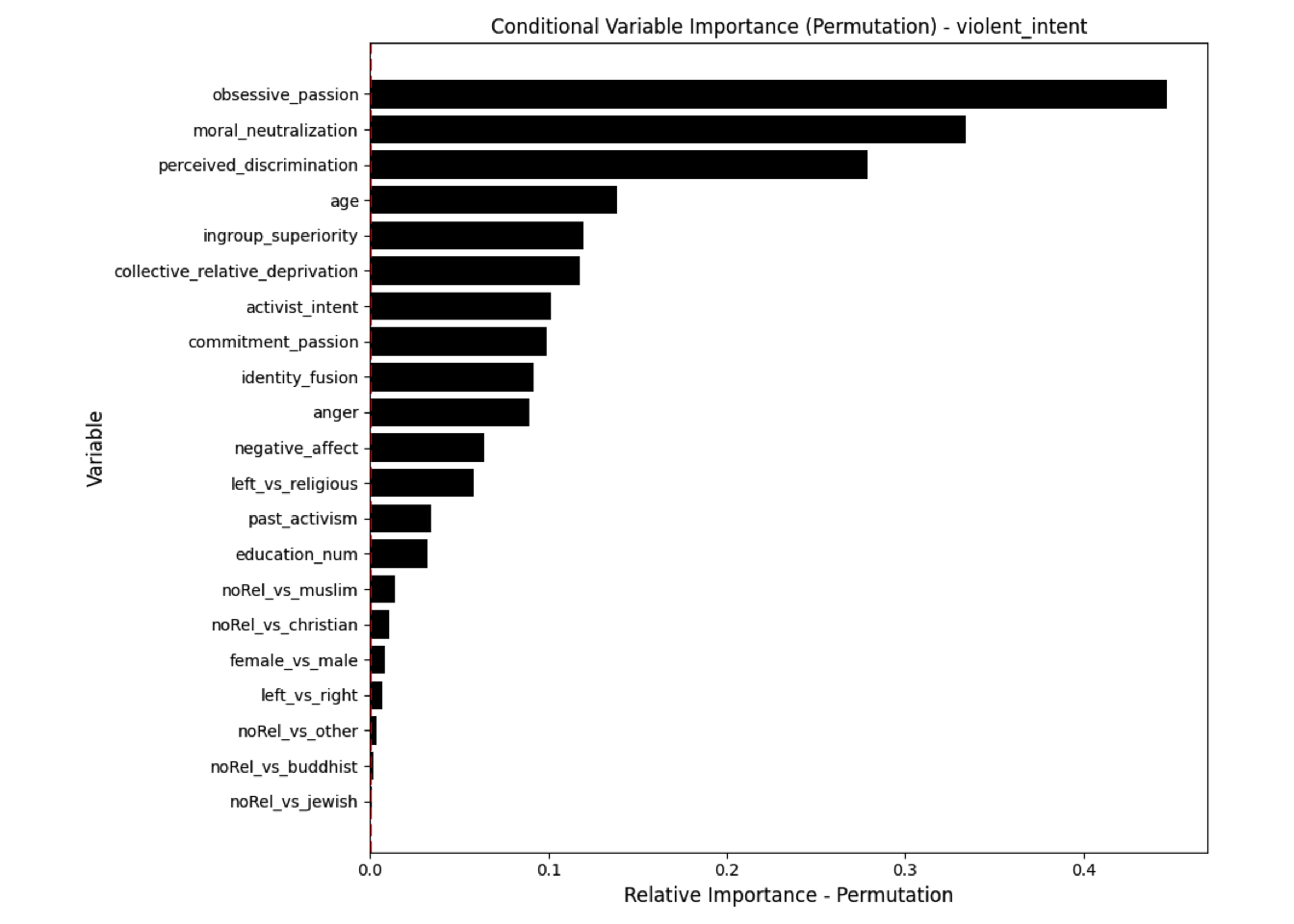

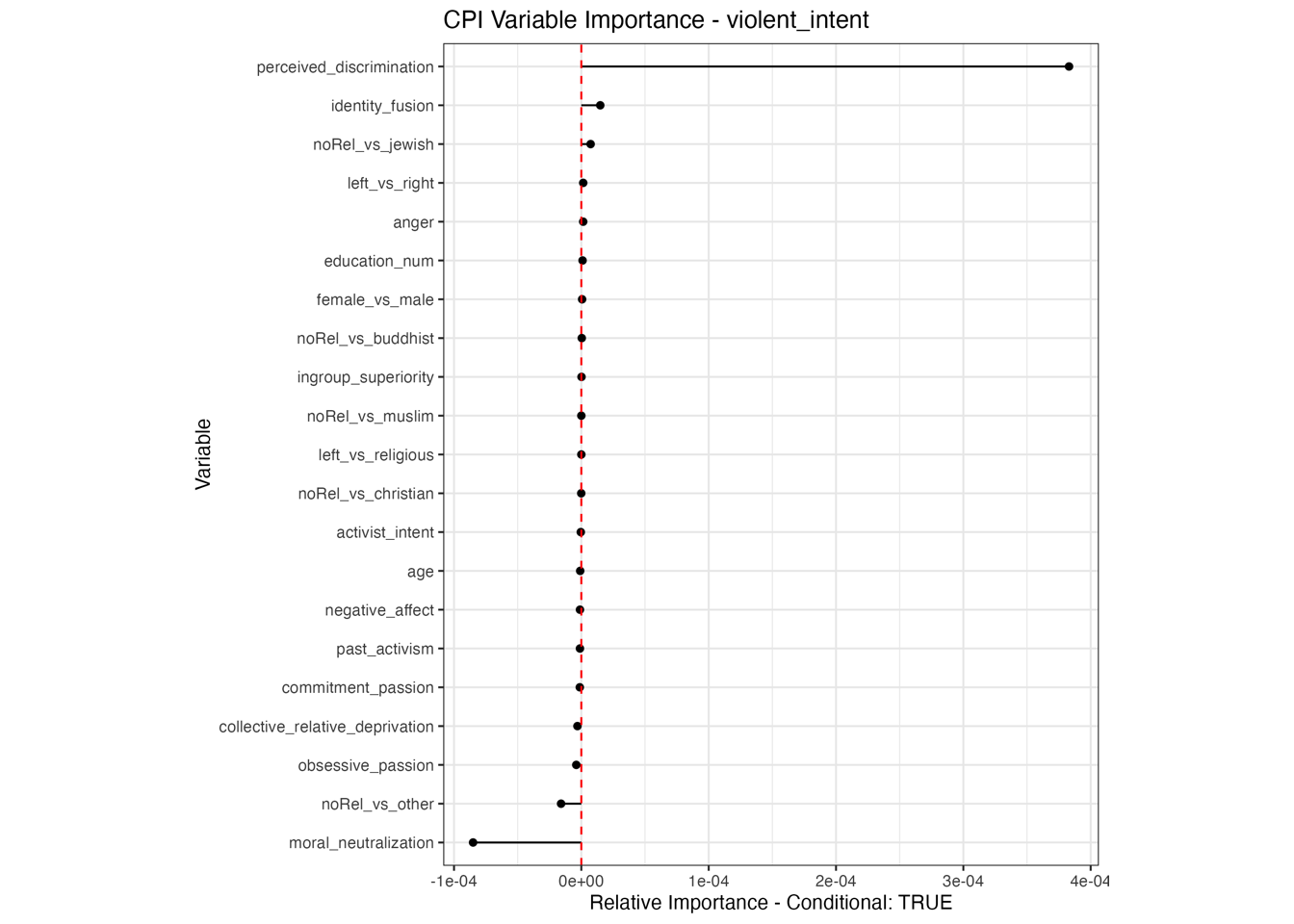

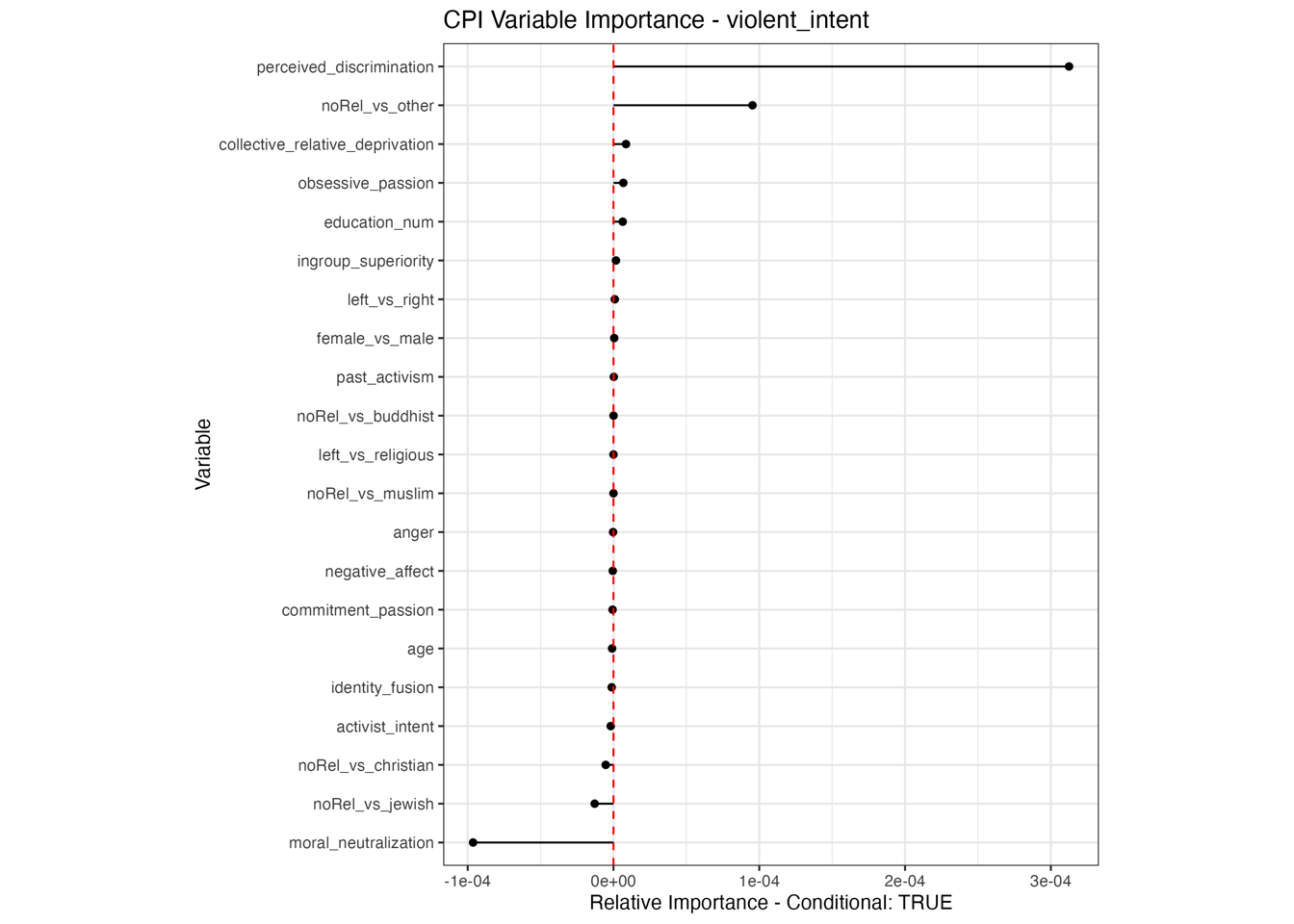

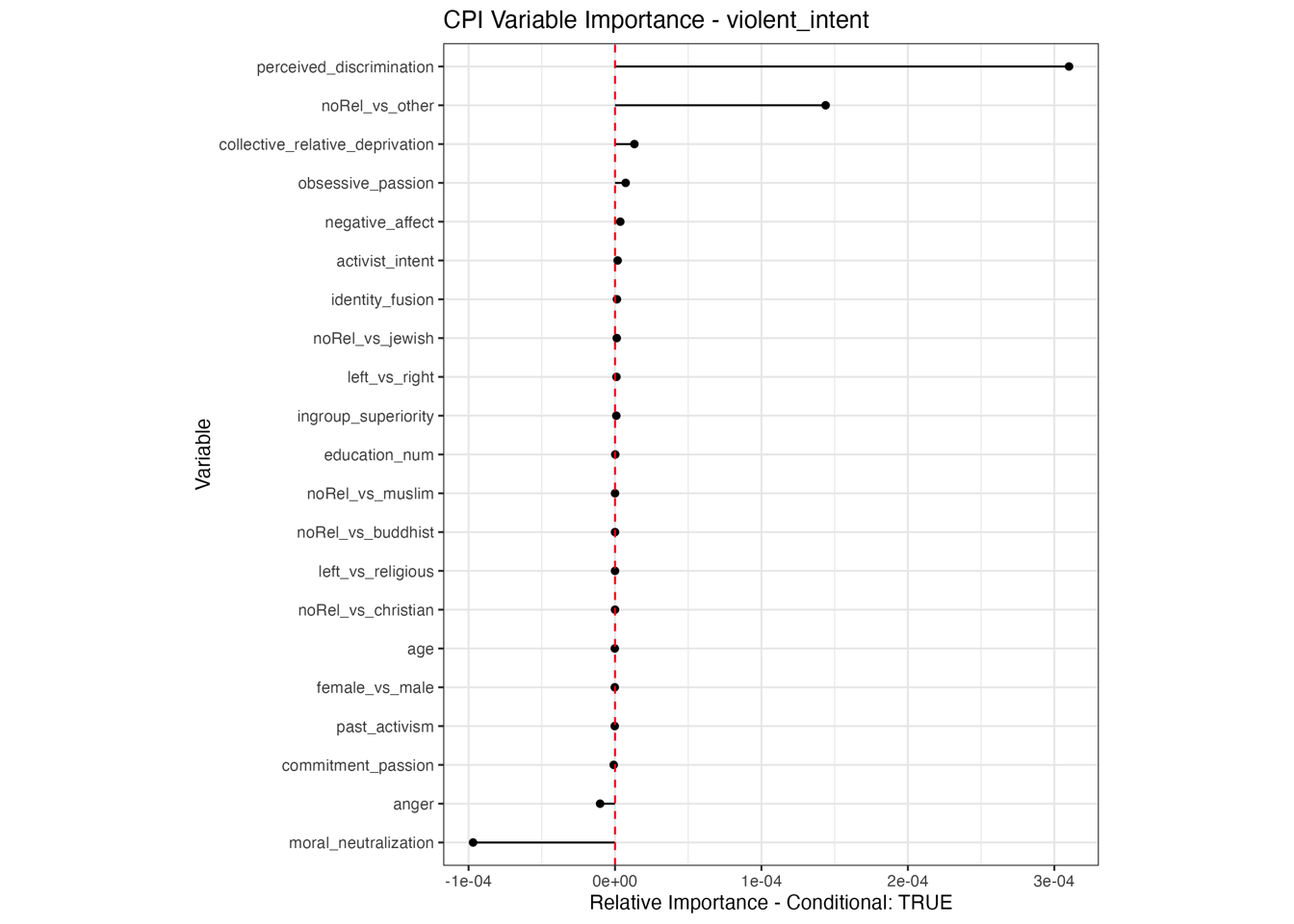

Negative values in Variable Importance plots

Interestingly, permutation variable importance can result in effects being negative. This suggests an actually improved model fit. Can be due to random Noise or Overfitting: If a predictor (X) is not really helpful for making predictions but is included in the model, it might introduce noise. When you shuffle (or permute) X, you remove the noise, and the model can make slightly better predictions. Can also be due to interaction Effects: Sometimes, a feature (X) may have complex interactions with other features (Z) in the model. When you permute X, it could disrupt these interactions in a way that ‘untangles’ some relationships in the model, leading to better performance.